Women’s Activism in Pakistan

In the earliest years following Pakistan’s formation, women’s activism generally followed a relation of mutual benefit and cooperation with the state with actors such as Begum Rana Liaquat Ali occupying key roles. Political resistance did not frame the debates surrounding activism at this stage as the main groups, such as the All-Pakistan Women's Association (APWA), relied on conversation with state officials.

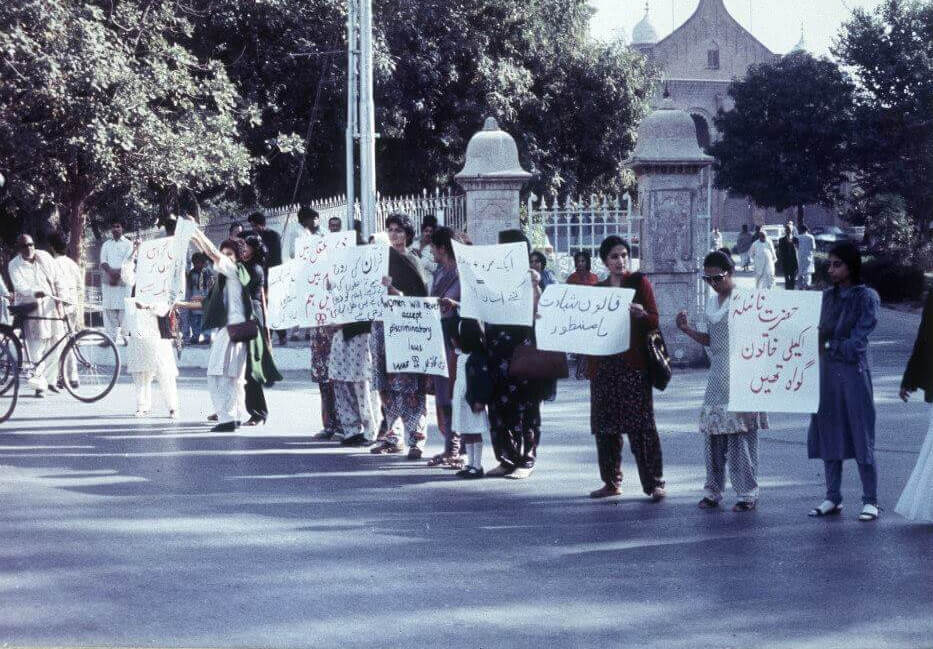

In the 1970s, organizations such as the Aurat Foundation and Shirkat Gah emerged when General Ayub was in power. These would be foundational in establishing later organizations pivotal to the women’s movement in Pakistan, such as WAF. The year 1979 represented significant upheaval for Pakistan as it found itself immersed in the global Cold War on the Afghanistan front. General Zia used this to legitimize his rule by introducing a rapid Islamisation program. This included the institutionalization of discrimination against women and other minority groups. Amongst the changes introduced were the Hudood Ordinances of 1979 which altered the status of women’s testimonies in courts and the definition of consent. Other forms of non-legal directives, which attempted to police women’s morality and sexuality with the enforcement of purdah, were similarly introduced. A milestone in transforming the prior relation between the state and women was the Allah Bux and Fehmida case, the first conviction under the Hudood Ordinances. The previous relation of cooperation with the state was transformed into an organized form of resistance.

The Women’s Action Forum (WAF) was formed as a response to these changes by women whose families had been a part of earlier forms of feminist activism. The membership comprised of primarily professionally trained women. While members of the organizations may have previously enjoyed a symbiotic relation with the state, in this historical juncture they could no longer depend on the same sense of security. As the main threat emerged from the state itself, the nature of activism which WAF performed changed fundamentally from previous groups. It defined itself as ‘non-political,’ in that sense, which meant not allying with any political party. It was successful in creating links between different feminist organization and a network which could be relied upon for action in the future.

The end of the Cold War in 1989 signaled a new era in global politics, with the rise of neo-liberalization. This change was paralleled with the return of parliamentary democracy in Pakistan following General Zia’s death. In the context of women’s activism this meant an influx in non-governmental organizations funded by western countries with the larger aim of ‘development’. NGOS, with their emphasis on development and the need to cater to the donor’s vision of politics, dampened some of the more radical edge of the resistance developed by groups. More structural analyses of how patriarchal oppression was institutionalized, particularly from socialist feminist lens, dissipated in favor of creating a mold of development which could be compatible with the NGO model. The nature of advocacy changed from street-based mobilization to a more subdued political engagement. However, some organisations, such as ASR, were still doing valuable work during this time as they became the subject of ire from Nawaz Sharif’s ministers.

The 1990s represented a period of both conflict and cooperation with the respective governments for women activist groups. Benazir’s government brought the First Women’s Bank and the opening of women’s police station which were seen as positive changes. Moreover, groups worked with the government to write the report for the Beijing Conference where Pakistan’s participation was seen as historical. In contrast, Nawaz Sharif’s proposed 15th Amendment which granted the power of interpretation of the Shariat to the Prime Minister was met by protest by the same groups.

The early 2000s followed the global war on terror with the attack on the twin towers. In Pakistan, this coincided with the rise of General Pervez Musharraf’s military dictatorship. General Musharraf introduced a rhetoric of liberalization which appealed to the elite which comprise the civil society in Pakistan. Musharraf sought to legitimize his rule by introducing changes which would be welcomed as liberal and necessary by the elite. NGOs underwent an influx in donor funding during this period as organizations such as the Aurat Foundation conducted programs to train women councilors. Funding was selectively granted to those organizations which were sympathetic to the General which further depoliticized the women’s movement.

Bibliography

Saigol, Rubina. Feminism and the Women’s Movement in Pakistan. Actors, Debates and Strategies. Friedrich Ebert Foundation, 2016.

Khan, Ayesha. The Women's Movement in Pakistan: Activism, Islam and Democracy. I.B. Tauris, London, 2018